Updates

ACT NOW! Submit your story to ArtLeaks and end the silence on exploitation and censorship! Please see the submission guidelines in the "Artleak Your Case" page

Submitted and current instances of abuse are in the "Cases" section

To find out more about us and how to contribute to our struggles, please go to the "About ArtLeaks" page

Please consult "Further Reading" for some critical texts that relate to our struggles

For more platforms dedicated to cultural workers' rights please see "Related Causes"

For past and upcoming ArtLeaks presentations and initiatives please go to "Public Actions"

by Pelin Başaran and Banu Karaca

Last year, the exhibition Here Together Now was held at Matadero Madrid, Spain. Curated by Manuela Villa, was realised with the support of the Turkish Embassy in Madrid, Turkish Airlines and ARCOmadrid. But in the exhibition booklet, the explanatory notes to artist İz Öztat’s work “A Selection from the Utopie Folder (Zişan, 1917-1919)” was censored upon the request of the Turkish Embassy in Madrid, and the expressions “Armenian genocide” and the date “1915” were taken out.The case shows how the Turkish state delimits artistic expression in the projects it supports, and how it silences the institutions it cooperates with.

After Turkey was chosen as the country of focus for the 2013 edition of the ARCOmadrid International Contemporary Art Fair, the designated curator Vasıf Kortun and assistant curator Lara Fresko started to work with the galleries that would join the fair. They helped in fostering connections between the Madrid arts institutions and artists in Turkey; as well as with the embassy officers in charge of the financial support of events such as Here Together Now, which would run as a parallel event to the main fair. The embassy indicated that it would support this exhibition with the generous sum of €250,000. However, it did not provide any written documentation guaranteeing this support, and outlining the mutual duties and responsibilities of the parties involved. Likewise, during the realisation of the project, there was no written communication between the embassy and Matadero Madrid, and all negotiations took place verbally, over the phone. It was in this manner that, from the very beginning, the state kept the exact conditions of its support ambiguous and created a tense situation for the organisers. Ultimately, this working practice gave the Embassy the possibility of denying the promised support, in the event that their request was not carried out.

This is not the first case of the Turkish state censoring an arts event it sponsors abroad. We frequently hear about such cases off the record, and at times through the media. One of the best-known cases of state intervention took place in Switzerland, during the 2007 Culturespaces Festival. Director Hüseyin Karabey’s film Gitmek – My Marlon and Brando, which had received support from the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, was taken out of the festival program at the very last minute, at the request of an officer from the General Directorate of Promotion Fund, on the pretext that “a Turkish girl cannot fall in love with a Kurdish boy” as was the case in the film. The officer threatened the festival organisers with withdrawal of sponsorship totaling €400,000 — much like the case of the Madrid exhibition. The festival director decided that they could not go ahead with the event without this support, ceded to the censorship request, and accepted to take the film out of the program. However, independent movie theaters in Switzerland criticised this decision and ended up screening the film independently of the festival.

Both examples show that the state controls the content of the projects it sponsors abroad, interferes with the organisations on arbitrary grounds, and violates artists’ rights by threatening the very institutions it collaborates with.

The administrative channel for the state’s support to events outside of Turkey is the Ministry of Culture and Tourism’s Promotion Fund Committee, established under law 3230 (10 June, 1985) with the aim of supporting activities that “promote Turkey’s history, language, culture and arts, touristic values and natural riches”. The Committee reports directly to the Prime Minister’s office, and is presided over either by the Prime Minister himself, the Vice Prime Minister or a minister designated by the PM. It has five more members: Deputy Undersecretaries from the Prime Minister’s Office, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, as well as the general managers of the Directorate General of Press and Information, and the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT). The objective of the fund is “to provide financial support to agencies set up to promote various aspects of Turkey domestically and overseas, to disseminate Turkish cultural heritage, to influence the international public opinion in the direction of our national interests, to support efforts of public diplomacy, and to render the state archive service more effective”.

The Committee convenes at least four times a year upon the invitation of its president to evaluate project applications. The only criterion in accepting a project is whether it complies with the objectives mentioned above. After the Committee carries out its evaluation, the projects are put into practice upon the approval of the PM. Representative offices of the Promotion Fund Committee monitor whether the projects are implemented in compliance with the principles of the fund. In the case of the Madrid exhibition, the Turkish Embassy assumed the role of representative office. In this respect, as per the relevant regulation, the embassy was in charge of controlling the project, signing protocols with project managers to outline mutual duties and responsibilities, making the necessary payments, and delivering the project report to the Committee. As such, the embassy’s avoidance of all written documentation is in breach of the principles and modus operandi established by its own regulations.

Overall, it can be said that the Promotion Fund Committee does not meet the criteria of transparency and accountability generally expected from a public agency. The dates when the committee convenes to evaluate the projects are not announced, and the committee members, annual budget, sponsorship priorities and selection criteria are not made public. The sums paid to projects sponsored and the content of the projects are not disclosed officially. In other words, there is no transparency about the distribution of the funds, or about the auditing procedures. Such structural problems make it even harder to reveal and question the state’s violation of the right to artistic expression.

Another important aspect of this case is that the state constantly tries to reproduce its dominant discourse based on the denial of past and ongoing human rights violations such as forced displacement, genocide, political murders, burning of villages, enforced disappearances, rape, and torture through security forces; and does its utmost to silence any expression which contests this discourse. The centenary of the Armenian genocide, 2015, is drawing near. As such, it becomes even more important to demand that the Turkish state be held accountable for this human rights violation.

Map of Cennet/Cinnet (Paradise/Possessed Island). Zişan, 1915-1917. Ink on paper, 20×27 cm

Siyah Bant is a research platform that documents and reports on cases of censorship in arts across Turkey, and shares these with the local and international public. In the context of this work, we wanted to investigate the censorship that occurred at Here Together Now. In accordance with the Right to Information Act, we asked the Turkish Embassy in Madrid and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, to explain the legal basis of the censorship they imposed on the booklet. In response, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism indicated that Matadero Madrid and curator Manuela Villa were the only authorities in charge of selecting the artists who would participate in the workshops of ARCOmadrid, designating the content of the works to be produced during the workshops, and preparing all printed matter in connection to the event. We were unable to obtain an official statement from curator Manuela Villa, despite several inquiries. Finally, we conducted an interview the artist İz Öztat to understand how the censorship took place, and how she experienced the process.

How did you come to be involved in the exhibition?

I was invited by Manuela Villa, curator of Matadero Madrid, after meeting her in Istanbul. Matadero planned for a residency program and an exhibition project titled Here Together Now to take place concurrently with the 2013 edition of the ARCOmadrid Art Fair that had a section consisting of invited galleries from Turkey. By the time I signed the contract with Matadero Madrid, I knew that the project was partially supported by the Turkish Embassy in Madrid and Turkish Airlines.

Here Together Now was a process that allocated the resources with an emphasis on living and working together. Cristina Anglada (writer), Theo Firmo, Sibel Horada, HUSOS (a collective of architects), Pedagogias Invisibles (art mediation collective), Diego del Pozo Barrius, Dilek Winchester and I had six weeks together, during which we figured out common concerns, negotiated our relationship to the institution’s public, designed the working and exhibition space, collaborated and produced our works.

Can you tell us about the nature of contract with the institution and if there were any limitations indicated as to the nature of your work?

We signed a very detailed contract with Matadero Madrid that laid out the responsibilities of the institution and the artist in relation to the production and authorship of new work but there were no limitations outlined in the contract. I took it for granted that the artist has freedom of expression and institutions do not interfere in the produced content.

The institution was extremely supportive of the project. They were engaged in our discussions and ready to help once we started producing the work.

Could you talk a bit about the work that you prepared for Matadero Madrid?

The work shown in the Here Together Now exhibition was part of an ongoing process, in which I imagine ways to conjure a suppressed past. Since 2010, I have been engaged in an untimely collaboration with Zişan (1894-1970), who is a recently discovered historical figure, a channeled spirit and an alter ego. By inventing an anarchic lineage with a marginalized Ottoman woman, I try to recognize a haunting past and rework it to be able to imagine otherwise. For the exhibition at Matadero Madrid, I produced and exhibited “A Selection from Zişan’s Utopie Folder (1917-1919)” accompanied by works from the “Posthumous Production Series”, in which I depart from Zişan’s work to open a path towards the future in our collaboration. The exhibited work was complemented by a publication with three interviews, which situates the work and builds a discourse around it.

Which aspect of the work was censored? How did the process of censorship occur, and what kind of dilemmas did you face in this process?

Manuela Villa, the curator, met with me in the exhibition space one evening a few days prior to the opening. Officials from the Turkish Embassy had threatened to withdraw their financial support, if the demanded changes were not made. I had to make a decision on the spot and accepted the censorship in the booklet, but not in the publication complementing the work. The exhibition booklet was reprinted and the sentence was changed to “Zişan, born in Istanbul in 1894, is a marginal woman of Armenian descent, who embarks on a European quest.”

As I said before, there was an emphasis on the community we built together during the residency at Matadero and I didn’t want to make a decision alone that would put the whole project at risk. Because of the time constraints, we were only able to meet with the other artists after the opening to discuss the precarious condition that we were all in. The institution didn’t have any signed documents from the Embassy committing to the sponsorship. Everything was communicated verbally and there was no written documentation. I was not able to reach out for a support network to resist the situation, not least due to the immediacy the decision required.

The exhibition booklet that was presented to the embassy was altered but the publication accompanying your work remained unchanged. How did the curator and other artists react to your refusal to change the publication?

I could not stand my ground with regard the exhibition booklet because it concerned everybody in the project. Yet, I was able to take full responsibility of my own work. We were informed that officials from the embassy will visit the show prior to the opening and I was ready to withdraw the work, if there was any interference. Everybody was supportive of my decision.

What happened on the day of the opening? Did you feel the need to prepare yourself?

In the end, none of the officials from the embassy came to the opening or the exhibition. There was no confrontation regarding the work. There might be a few reasons for this that I can think of. Maybe, they felt entitled to interfere with the content of the exhibition booklet because it had the logo of the embassy and could dismiss my publication since it only had the logo of Matadero Madrid. It was not of benefit for the embassy to confront me in a situation that would have made the case public.

As Siyah Bant we inquired both with the curator and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in order to understand how this censoring motion played out. Given that the ministry rejects any responsibility and instead assigns all responsibility to the curator, and that the curator was acting under the duress of loosing all funding last minute, where does this leave you as the artist? How do you make sense of what happened to your work?

Since I accepted the censorship, my only option was making the situation public after the fact. I have been working in cooperation with Siyah Bant since I got back from Madrid. It took a few months to receive an official response from the embassy, which denied all responsibility. We wanted to make the case public after receiving a statement from the curator or the institution. I was unable to receive such a statement, and Siyah Bant is working on that now.

I see it as an experience, in which I was able to test and see the boundaries of government support that is allocated to arts and culture for promoting the country. If you decide to accept this support and challenge official policies, a system of censorship starts to operate.

Next year marks the centenary of the Armenian genocide which will inevitably bring about numerous artistic and cultural reflections on the subject. Given the current climate in Turkey, how confident are you that artistic freedom of expression will be respected?

We are going through a period, in which it is impossible to make predictions about what can happen even the next day. I can only hope that genocide denial at state level comes to an end. I am sure that artists will articulate their own ways of recognising the Armenian Genocide and confronting its denial. You are probably more prepared than I am to predict and know what kinds of mechanisms are at work to limit the production and dissemination of such work.

What would be your recommendations to other artists taking part in cultural events that are supported by the Turkish government?

Based on my experience, I think that artists and art institutions need to act in solidarity in these situations. If there is funding from the Turkish state, the institutions and artists involved need to be aware that the state monitors the content. The various institutions that distribute state funding do not provide written documents about their commitments and communicate their demands mostly in person or by phone. Demanding written documentation at every step is necessary. Artists who are considering to take parts in projects that receive state funding, can demand from the art institutions to be more transparent about the budget and its workings so that they can be prepared to make alternative plans if the state funding does not come through as promised.

If I encountered the same case of censorship now, I would not feel obliged to make a decision immediately and in isolation. I would consult the rest of the group and demand the involvement of the institution.

This article was posted on May 28 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

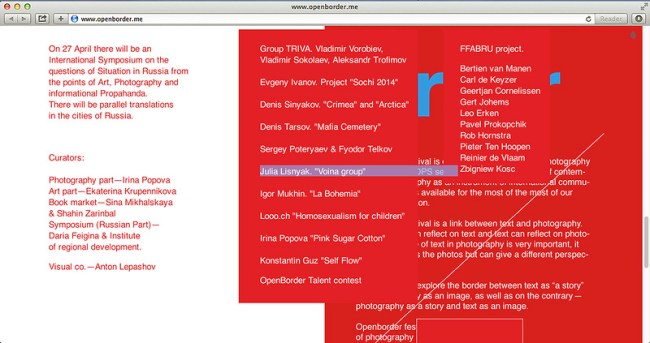

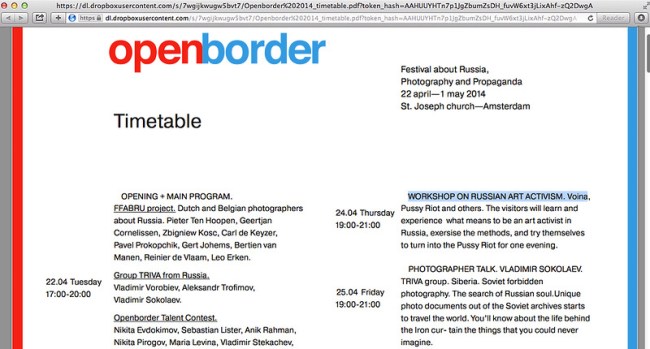

The Voina group protested against its inclusion on the list of participants at the festival OpenBorder which ran from April 22nd to May 1st in Amsterdam. The group justified their decision claiming that the festival was anti-Russian. On the site of the festival, the organizers state that “Russia has carried about an armed intervention in Crimea, Ukraine. And the independent medias in Russia are now closed or changed the directions. (Dozhd, Lenta.ru, etc.). The inner Russian information is more and more directed to the political propaganda, censorship and total informational control, like in the times of Iron Curtain.” The festival took place in in St. Josephkerk, Amsterdam. Its aim was to “bring the visual and cultural dialogue between Russian and the west trough an exhibition of photo projects and a series of events.”

Describing the above statement as “anti-Russian,” on April 13th the Voina group refused to participate in OpenBorder. One of the core members of Voina, Oleg Vorotnikov appealed to the festival organizers in an open letter, in which he outlined the reasons behind the refusal: “There are ideological reasons behind our categorical refusal…The Voina group has a fundamentally different opinion on Crimea, an opposite position to that of the organizers. We are glad that Crimea was annexed by Russia, and we are happy for the Crimeans. I am proud of my country for the first time in a long time. And that’s not all. For years I have criticized the unprofessional liberal media – in particular, “Lenta.ru” and “Dozhd”. I have often cited them as examples of prostitution, to the point of a humanitarian catastrophe in the Russian press. And finally, I welcomed their belated shrinking.

In general Voina’s position is the very opposite off all that is expressed by the organizers of the Dutch exhibition,” concluded Vorotnikov.

On April 23rd, the Voina group posted on its official website that, “despite the curators’ promises, Voina’s name has still not been erased from the schedule.” “Even after Voina’s loud statement and a long correspondence, the organizers are still trying to ignore the obvious: the Voina group is not participating in any foreign anti-Russian demonstrations!” declared the group.

The Russian artists list on the OpenBorder Festival website

The posted schedule of the OpenBorder festival on April 24th

Irina Popova, one of the curators of the festival replied to Voina that “the workshop will mention the Voina group, and it will not be led by them. It is a big difference. We have enough information from public sources, which no one can prohibit us from using, since it is for educational and research purposes.” Popova qualified Voina’s statements as “baseless attacks.”

In a conversation with Colta.ru, the organizers of OpenBorder further responded to Voina’s accusations: “This a gross misconception. We love Russia, and we are very worried about our country, otherwise it would not be the central theme of our festival.” According to the organizers, despite the fact that the festival’s timeframe coincides with the annexation of Crimea and the crackdown on the free media, OpenBorder does not have political overtones, and it would be wrong to interpret it that way. They noted that the festival was carried out without any support from Russian or Western organizations, and it is supported only by the Dostoyevsky Photographic Society. The main theme of the festival was “Photography and propaganda,” however the organizers claim they did not advocate for one side or the other, rather their aim was to analyze the phenomenon of propaganda: “We as organizers do not make any comments on Crimea, or other issues , but only give various artists and groups a platform for expression and open dialogue, if it is still possible. We function only on a cultural plane, the only thing which we stand for is freedom of creativity, expression and exchange of information. Culture – is something that will outlast policies and regimes, that’s what we call value and respect.” stated OpenBorder organizers. They also shared that at the end of the festival they were planning to establish photographic and artistic connections between Russia and the rest of the world, believing in the power of dialogue.

Concerning the conflict with Voina, the organizers remarked: “We sincerely regret that Voina refused to take part in the festival; they have ignored this opportunity for dialogue, and expressed their point of view in the form of provocative and erroneous statements that the media automatically reproduced.” They continued that they are entitled to analyze Voina’s public activities for research and educational purposes, using publicly available sources and documentary stories previously published. “We are sincerely sorry that Voina lost much of the public’s interest in their activities and use every opportunity to stir up such scandals.”

Text based on an articlez published on Colta.ru (in Russian) and on texts publicly available on the Voina site.

MAYDAY: Art Workers’ Pride Visual Archive

This Thursday is May Day, international workers’ day.

Across the globe workers will celebrate May Day in various ways, organizing street demonstrations and protest marches in their communities, demanding justice and freedom for all oppressed people.

With this occasion, ArtLeaks will inaugurate a visual archive dedicated to art workers’ pride, which will continue to gather material throughout the year.

We invite you to submit visual documentation of protests/performances/comics/banners/short texts related to art and cultural struggles. Please send the material to artsleaks@gmail.com or @Art_Leaks, including the credit information and a title or very short description. Both signed and anonymous entries welcome.

Our aim is to create a visual archive of different actors and movements around the globe focused on art labour. We think this is will grow into a great resource and encourage all persons working in art and culture to submit their materials to this public archive.

Happy May Day International Workers’ Day!

______________________________________________________________________

Thanks to all the contributors so far and please continue sending us materials! The archive holds historical cases of art workers’ organizations and struggles from the late 19th century to the present! This is a selective history, not a comprehensive one – we will update the archive regularly !

To view the archive full screen press on the arrows button on the lower right corner.

In February 2014, the Bucharest based artist Alexandra Croitoru was invited to present a selection of works from her 2004 portrait series “Powerplay” in an exhibition on gender relations, part of the Summer of Photography at De Markten, Brussels. Sam Gilbert, the coordinator of the event, explained to the artist that the festival always relies on foreign cultural centers for financial support, so they were planning to collaborate with the Romanian Cultural Institute (thereafter RCI) in Brussels, as they had in previous years. In one of his initial emails, Gilbert expressed some concerns stating that “as we understand the portrait with the former prime minister [of Romania, Adrian Năstase]* might be a bit controversial” and suggested that they would continue to discuss the selection of Croitoru’s works.** The image in question is part of a series of self-portraits with men of power in Romania, including the MC’s of a popular hip-hop band, TV stars and the former prime minister, all looking away from the camera. Curator Mihnea Mircan wrote in a text in 2004 that the double portraits “produce an active object of power and an activity that is not confrontation but a transversal effort of contamination, showing also a strangely monumental quality.”

After the correspondence with Gilbert, Croitoru emailed Cătălin Hrişcă, the coordinator for visual arts and film at the RCI in Brussels, with whom she was already in contact, asking him weather he was the one who suggested to Gilbert that including her portrait with the prime minister Năstase in the exhibition would be problematic in the context of the collaboration with the RCI. Hrişcă replied that there must have been some misunderstanding: he would have never dared make such a suggestion, and moreover he stated that he was the one who suggested Croitoru to the festival organizers. Hrişcă did admit that he had asked Gilbert weather he knew who the man in the portrait was, and concluded that this may be why the latter had jumped to conclusions. Finally Hrişcă stated that the RCI Brussels respects the artists and their works, and never intervenes or influences the artistic process. “Of this I can assure you.” he ended the email.

Later that month, Gilbert and Croitoru made a selection of four works to be shown in Brussels. Gilbert informed the artist that, for the financial aspects of production, namely production, transportation, insurance and the artist fee, she should discuss directly with Hrişcă. Croitoru wrote to the latter herself, informing him that a final selection of works has been made and she would like to know more details about the contract with the RCI. Hrişcă replied that he was in contact with the organizers of Summer of Photography and they informed him that she will be exhibiting the four photographs. He also told her that the project would be analyzed by the directorial committee of the RCI in Bucharest but only on March 15th, 2014. The funds would come from the general RCI fund, after an internal competition between projects proposed by different RCI representatives. He also stated that he was working on an internal memo to emphasize the importance of the project. Hrişcă assured Croitoru that they will do everything in their power to finance the project and that he didn’t foresee any problems why they shouldn’t, but that he has to follow the RCI’s internal protocols.

However, problems did arise. In a recent email Hrişcă sent to Croitoru, he stated that he regrets the fact that a consensus about the collaboration wasn’t reached yet, probably for “technical reasons” – it was true that some of their emails didn’t reach her. Referring to the exhibition “Gender Relations” during the Summer of Photography festival, he confessed to her that if the RCI were to support the exhibition of a photograph showing the politician Adrian Năstase, given the current electoral season, this may be “interpreted in a wrong way, as a political message”; thus, it would be against RCI internal protocols and would have a negative impact upon their institutional activities. He suggested her to replace the photograph featuring the former prime minister with another one from the series.

In a previous email, Nora de Kempeneer, coordinator of the De Markten, the institution where the exhibition will take place, emailed Croitoru stating that “it was with astonishment that the institution learned there was a misunderstanding” between Croitoru and RCI and that they appreciate “the efforts of Mr. Cătălin [Hrişcă] to present artists from Romania in Belgium,” but also the institution she represents respects “the opinion and freedom of the excellent artist Alexandra Croitoru who defends a case.” She suggested the RCI and the artist should solve the problem whether or not the portrait with the former prime minister should be presented in the exhibition. She also stated that the topic of the exhibition was gender and the role artists play in defending the position of women in contemporary society and that it was difficult for De Markten to estimate the political message behind Croitoru’s image since they were not familiar with local Romanian politics. De Kempeneer ended stating that the institution she represents prefers to stay impartial and let the artist and the RCI resolve the conflict.

After these emails, Croitoru wrote to de Kempeneer and Hrişcă that she decided not to participate in the exhibition given the above-mentioned facts. She also asked them not use any materials she had sent in previous emails and informed Sam Gilbert that she is withdrawing from the exhibition and, as they had b88een discussion the possibility of using the title of her series “Powerplay”as the title of the exhibition, this would not be possible anymore.

Alexandra Croitoru, From the Powerplay series:

* Adrian Năstase is a Romanian politician who was the Prime Minister of Romania from December 2000 to December 2004. He was the President of the Chamber of Deputies from December 2004 until March 2006, when he resigned due to corruption charges. In January 2012, the courts gave Năstase a two-year prison sentence for misuse of a publicly funded conference to raise cash for his unsuccessful campaign in 2004. In January 2014, the Romanian Supreme Court sentenced him to a four-year prison sentence for taking bribes and a three-year prison sentence for blackmail, to run concurrently.

** All quotes thereafter are from the email conversations between Croitoru, Gilbert, Hrişcă and de Kempeneer unless otherwise noted.

Starving Artists Fed Up; Seek To Establish Industry Standards With Teamsters Local 705 (Chicago, IL)

UPDATE

Artists Aim for Union Precedent Same Day as Northwestern Football Players

(Chicago) – Art handlers with Mana-Terry Dowd LLC may set an industry precedent this month by being the first employees of a major art transportation company in Chicago to unionize.

Approximately 31 high-end art handlers will vote whether to join Teamsters Local 705 on April 25 — the same day Northwestern University football players also could change the face of union membership by organizing with the College Athletes Players Association. Like Northwestern’s group, the majority of Mana-Terry Dowd workers are young professionals — art graduates in their mid-20s and 30s eager to set standards where they work.

The art handlers, who transport and install priceless works for anyone from private collectors to the Art Institute of Chicago, represent the latest in a national trend to organize the art world. In 2012, 42 Teamsters at Sotheby’s in New York ended a 10-month lockout with a three-year union contract. In 2011, Teamsters as well negotiated higher starting salaries for workers at Christie’s auction house.

Most recently, the Teamsters reached a deal on April 9 with Frieze New York, one of the city’s most successful art fairs, to begin using union labor at the high-profile event. For Mana-Terry Dowd employees, Chicago’s expansive arts community is the next logical destination for unionization.

“If not now, when?” said 24-year-old Chloe Seibert, who works in Mana-Terry Dowd’s Logan Square warehouse. “Because we’re seen as artists and not laborers, a lot of workers in the art industry aren’t being compensated properly for the job they do. Employers today have a large pool of applicants to choose from and unfortunately big private companies tend to take advantage of that. They know they can get away with giving you less.”

Wages for Mana-Terry Dowd workers begin at $14 per hour, though more than 70 percent of its workforce walks in with a Master’s degree. For 27-year-old Neal Vandenbergh, who’s been with the company for 18 months, wages for art industry jobs fall far below the costs of education and certification needed to obtain them.

“Young people are expected to begin their careers this way — at a minus financially. Graduates entering the job market are saddled with debt,” said Vandenbergh, who works in all aspects of art transportation, from truck driving to exhibition. “This industry needs a union voice. Labor standards haven’t caught up to the speed at which the art market in America has grown.”

While employees want fair wages in the industry, worker mistreatment is at the forefront of the Mana-Terry Dowd union campaign. The Teamsters have several unfair labor practice charges against the company pending before the National Labor Relations Board. Management has been charged with threatening to fire or discriminate against workers who support the union, threatening to eliminate positions entirely, interrogating employees and purposefully including supervisors in the bargaining unit of eligible voters.

For art handlers trying to improve workplace conditions, joining the Teamsters only makes sense.

“These are well-educated individuals performing physically demanding jobs. In cities like New York and Chicago, the Teamsters have established industry standards for thousands of workers in transportation, whether our members are behind the wheel of a truck or moving commercial property,” said Juan Campos, Secretary-Treasurer of Local 705. “Mana-Terry Dowd employees are taking a stand where there typically haven’t been many protections for workers. It’s a noble effort.”

Terry Dowd has handled fine art and artifacts since 1978, but the company merged with Mana Contemporary LLC in February to form the current venture. Its employees routinely move work for Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art and travel regionally for larger installations, such as a recent move of the University of Missouri’s Museum of Art and Archeology collection.

Seibert just moved mixed-media American artist David Hammons’ glass basketball hoop, which sold at auction in 2013 for $8 million. It’s just the kind of workload that speaks volumes to the art handlers’ need for union representation.

“Who is a stereotypical union member? A builder, a mover, a truck driver?” Seibert said. “As art handlers, we do all of that and more. Forget the stereotypes. I want to have a say in my wages and working conditions, to be included in the conversation. I want to take hold of my future.”

____________________________________________________________________

Art School Graduates Seek a Teamster Local 705 Contract at Mana Terry Dowd

Chicago— 04/08/14 — Teamsters and artists may seem like an unlikely combination, but professional artists at Chicago’s Mana Terry Dowd fine art packers and movers are organizing in an effort to begin to establish income and benefit standards in their profession. The artists are set to vote on April 25 in an election administered by the National Labor Relations Board. Upon graduating with a degree in art, professional artists are faced with few employment options. Even after receiving debt-burdening advanced degrees, these highly talented and skilled artists vie for a professorship or to make it big in the art scene. In the meantime, postgraduate artist are typically faced with two remaining low-wage choices; to work as an assistant at an art gallery, or to become an art handler as with Mana Terry Dowd. These jobs often pay little more than fast- food wages.

Companies like Mana Terry Dowd hire well-educated professional artists for the packaging and moving of pieces of fine art. Mana Terry Dowd knows that their art handlers treat their customer’s property safely and with respect. However, these artists who move these pieces don’t make enough to survive; yet the job options available are so limited that they have little choice but to continue working in adverse and difficult working conditions in which they are not viewed as professionals.

Mana Terry Dowd is opposing the Teamsters’ efforts to help professional art handlers in making their job one they can thrive in. Mana Terry Dowd is suspected of including managers and supervisors as eligible voters in the upcoming election in an effort to undermine the art handlers’ organizing efforts. Teamsters Local 705 plans to challenge Mana Terry Dowd’s actions at the National Labor Relations Board, but often even that doesn’t stop Mana Terry Dowd and companies like them from dealing dirty with their professional art handlers.

Do Teamsters and artists still seem like an odd pair? They aren’t; art school graduates are organizing with the Teamsters because it is time to stand up for their profession and demand the wages and benefits that a highly educated and skilled artist deserves.

Teamsters Local 705 Chicago